Si nota un rinnovato interesse per la musica bizantina. La sua struttura tradizionale. L’UNESCO l’ha definita “patrimonio immateriale dell’umanità” (English version at the bottom).

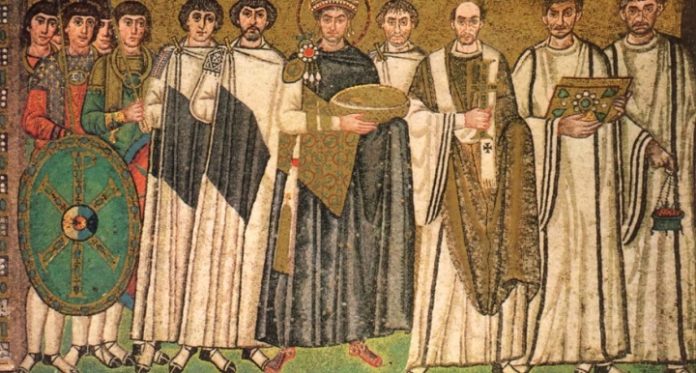

L’arte della musica bizantina è fondata su di un sistema di canto monofonico in possesso di un proprio criterio di scrittura. Le sue radici si ritrovano nel sistema musicale greco antico e nel canto ebraico biblico, ma la sua propria formazione è da ricondurre alla grazia del primo cristianesimo, in aree quali l’Asia Minore, il Medio Oriente e l’Africa Nordorientale. Anche se la musica bizantina è stata storicamente adottata sia da espressioni religiose che secolari, oggi è pressoché esclusivamente usata all’interno del canto sacro di molte delle Chiese ortodosse del mondo.

La popolarità è stata recentemente accresciuta dalla decisione dell’Organizzazione delle Nazioni Unite per l’educazione, la scienza e la cultura (UNESCO) di riconoscere la musica bizantina quale parte del «patrimonio immateriale dell’umanità». Questo importante riconoscimento giunge di fondamentale importanza per la preservazione della tradizione vivente dell’arte bizantina e offre, anche a coloro che non hanno familiarità con tale espressione di musica prevalentemente sacra, l’opportunità della conoscenza e dell’esperienza della bellezza.

La nota di accompagnamento

Per quanto riguarda la struttura, la musica bizantina ha come base otto modalità principali fisse. Tuttavia, all’interno di ciascuna modalità, sono comprese sottocategorie di suono diversificate. La musica eseguita all’interno di queste stesse categorie può offrire emozioni molto diverse, ad espressione della sorprendente ricchezza dell’arte musicale bizantina.

La musica della tipologia ecclesiastica è nota per la totale assenza di strumenti musicali.

Inoltre, sebbene in alcuni momenti della sua storia non sia stato raro incontrare singoli solisti impegnati nella intonazione di interi canti liturgici, la tradizione più antica vuole che sia l’intera comunità a cantare. Poiché oggi non tutte le persone sono addestrate all’arte musicale, è divenuta prassi ordinaria affidare a cori specialistici l’esecuzione liturgica dei canti.

A differenza dello sviluppo ecclesiastico avvenuto in alcune aree del mondo ortodosso, quali la Russia, o a differenza di casi più peculiari di influenza occidentale sulla musica bizantina, quali a Cefalonia in Grecia, il canto bizantino non è mai divenuto polifonico. Non contempla infatti una seconda voce completa in senso proprio, ma prevede una voce fissa sub-tonica, denominata isokratima, la cui funzione è quella di produrre una nota di accompagnamento costante durante il canto.

La parte di esecuzione di questa voce, a modo di “basso continuo”, è a volte percepita, anche all’interno dell’ambiente ortodosso, come ruolo minore. In realtà, è essenziale per la corretta espressione della musica bizantina. Benché la nota di accompagnamento in genere non vari durante il corso del canto, sono possibili vari esercizi di esecuzione ed esistono diverse scuole di variazione al riguardo.

Alcuni autori ed esecutori preferiscono che la stessa nota di accompagnamento sia di sostegno per l’intera durata del canto, mentre altri risultano più sensibili alla nota in mutazione nel corso dello stesso canto, al fine di raggiungere una più vasta gamma di suoni profondi. Oggi, si possono incontrare nell’esecuzione della musica bizantina entrambi questi approcci. Tuttavia prevale l’equilibrio ben rappresentato da leggere e occasionali modifiche alla nota di accompagnamento.

I neumi e i tempi musicali

A differenza della musica occidentale, in cui le note sul pentagramma possono essere precisamente individuate ed eseguite, nella musica bizantina ogni segno o neuma deve essere decodificato e interpretato in rapporto al neuma precedente. In una certa misura, questo rende l’esecuzione della musica bizantina più complessa, poiché, se si commette un errore nella lettura di un neuma, senza rendersene conto, si può continuare ad errare nell’interpretazione dei neumi successivi. Perciò, l’inizio di qualsiasi brano musicale bizantino, prevede un carattere identificativo della modalità in cui l’inno deve essere cantato. Ciò informa il canto per quanto riguarda la nota di partenza. Mentre i neumi successivi conducono a produrre le caratteristiche aggiuntive interne al testo musicale.

Un altro aspetto chiave della musica bizantina è che la stessa non è ben regolata nella velocità di esecuzione. Mentre la musica occidentale è tipicamente governata da un preciso tempo per ogni canto, attraverso la misura di un metronomo, ciò non avviene nella musica bizantina. Questa prevede, tuttavia, alcune categorie di tempo che, a priori, aiutano a condurre la velocità di un canto.

Le tre classificazioni sono così definite: a passo molto lento, a passo medio, ossia circa quattro note per ogni sillaba (sticherari), a passo più veloce. Spesso queste classificazioni sono strettamente legate al singolo canto liturgico in esecuzione, a meno che i canti non siano collocati nella stessa circostanza liturgica, quale una veglia estesa, e per ciò ricondotti alla stessa classe, in genere la prima, molto lenta.

Un viaggio nella storia

La musica bizantina si è sviluppata nel corso dei secoli da un’espressione molto semplice e monotona ad espressioni coerenti ma sempre più ricche e complesse. Ci sono poche e preziose testimonianze del primo periodo che va dal IV al IX secolo, dal momento che i manoscritti musicali bizantini dell’epoca sono quasi inesistenti. La stragrande maggioranza delle prove può essere dedotta solo da resoconti storici, sermoni o indizi rinvenuti all’interno di successivi libri liturgici. Tuttavia conosciamo alcuni esempi di inni sicuramente risalenti alla prima epoca, anche se la loro forma attuale risulta già un poco elaborata.

Durante l’epoca medievale, la musica bizantina non è cambiata di molto, a motivo del desiderio delle Chiese di restare fedeli alla tradizione tramandata. Solo a partire dal IX secolo sono conosciuti manoscritti musicali bizantini di tradizione innografica scritta.

Cambiamenti significativi sono avvenuti solo verso la fine del tempo dell’impero bizantino e durante l’occupazione ottomana degli ex territori bizantini. Questi cambiamenti hanno chiaramente unito elementi di conservazione ad altri di carattere più liberale.

Ciò che la ricerca storica oggi mostra con evidenza è che la notazione scritta si è fatta sempre più complessa sino all’inizio del XIX secolo, finché si è manifestata l’esigenza di semplificarne la modalità perché la musica bizantina risultasse più accessibile a coloro che desideravano studiarla ed eseguirla. Tale forma è rimasta sostanzialmente in uso sino ad oggi.

Ora, la musica bizantina guadagna di nuovo fascino popolare in varie regioni. Abbiamo un buon esempio di ciò oggi negli Stati Uniti. Circa trenta o quaranta anni fa la pratica prevalente nei servizi liturgici tra le parrocchie dell’arcidiocesi greca ortodossa d’America (Eparchia del patriarcato ecumenico di Costantinopoli) era orientata ad inni antichi adattati ad una partitura musicale polifonica.

Grazie ad alcuni membri della gerarchia aderenti alla sacra tradizione e al lavoro straordinario di diversi professori di canto bizantino, è aumentato l’interesse delle parrocchie a ritornare alla tradizione, si sono moltiplicate le conferenze di studio, è stato varato un programma di certificazione, mentre una nuova generazione di giovani cristiani greco-ortodossi sta diventando sempre più competente nell’ambito.

Anche al di là del mondo religioso ortodosso, la musica bizantina ha visto crescere di interesse, poiché è diventata più accessibile alla popolazione ed è stata posta al centro pure da contesti accademici. Registrazioni di canti delle comunità monastiche – quali le registrazioni dal convento di Ormylia in Grecia e dai monaci del Monte Athos –stanno offrendo a tutto il mondo la possibilità di ascoltare gli inni celestiali che la Chiesa ortodossa canta da secoli.

Una memoria da custodire

Con la recente decisione dell’UNESCO di riconoscere il canto bizantino come parte del patrimonio culturale immateriale dell’umanità, si può nutrire dunque la fondata speranza che una sempre maggiore conoscenza sia portata verso questa arte spirituale.

Per i cristiani ortodossi il canto bizantino costituisce un mezzo con cui lodare Dio ed essere portati in relazione più stretta con lui attraverso il divino culto. L’aspirazione a preservare il canto bizantino vede ora una partecipazione ampia anche da parte di coloro che non sono nella fede ortodossa.

Ma, mentre questa tradizione viene ripresa in più parti del mondo, le regioni da cui ha preso linfa – principalmente l’Asia Minore, il Medio Oriente e il Nord-est Africa – vedono diminuire amaramente la popolazione cristiana, spesso a causa di guerre e di persecuzioni. Perciò, la conservazione e la protezione della musica bizantina diventa la conservazione e la protezione della storia e della memoria di tante persone che, nel corso dei secoli, hanno praticato e vissuto la fede cristiana in questa precisa tradizione.

Nel lavoro di trasmissione dell’arte della musica liturgica bizantina è per ciò di fondamentale importanza riconoscere il coraggio di coloro che continuano a praticare questa sacra tradizione innologica, pur dovendo subire persino violenza a motivo della elevazione della propria voce di canto al Signore.

Il diacono Bartholomew Mercado è un monaco greco-ortodosso, greco di lingua e di cultura. Attualmente vive negli Stati Uniti. È un ottimo conoscitore dei neumi antichi e ne parla in modo autorevole.

The Byzantine psaltic art, also known as Byzantine music, is a system of monophonic chanting contained in eight principal modes and possessing its own written system.Its origins can be found in the Ancient Greek musical system and in Jewish chanting, but had its real formation in early Christianity in places such as Asia Minor, the Middle East, and Northeastern Africa. Though Byzantine music has historically been used in both religious and secular expressions, it is most popularly used today within the sacred chanting of many of the world’s Orthodox Churches. Its contemporary popularity has recently been heightened after the decision of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to recognize Byzantine music as a part of the world’s “intangible heritage of humanity”. This important designation is crucial to preserving the living tradition of the Byzantine psaltic art and it offers those who are not familiar with this expression of predominantly sacred music the opportunity to experience its beauty.

With regard to its structure Byzantine music has as its basis eight principal modes. Each of the first four modes has a “plagal” or variation of itself which is counted as a separate mode and, to the listener as well as the chanter, has a distinct quality from its counterpart. Nevertheless, even within these principal modes, there are subcategories which offer a diverse sound yet still, theoretically, being a part of the principal mode. Often times the music within these diverse subcategories offer a completely different emotion and, thus, enriches the psaltic art in general. Byzantine music of the ecclesiastical variety is also known for its complete absence of musical instruments. Furthermore, though there are times within its history when it was not uncommon for soloists to chant the hymns of the Church, the more ancient tradition is for the entire community to engage in chanting these hymns. Due to practical reasons today wherein not all people are trained in the psaltic art, it has become commonplace for choirs of Byzantine chanters to chant these hymns together.

Unlike later ecclesiastical music in some areas of the Orthodox world such as Russia or in more peculiar instances such as western influence on Byzantine music in Kephalonia, Byzantine chant is not polyphonic and, therefore, lacks harmony. Though there is not a full second voice strictly speaking, there is a sub-tonal voice called the “isokratima” the function of which is to hold the drone note during chanting. This is sometime perceived by some, even within the Orthodox milieu, as a minor role, but in actuality it is absolutely essential for proper Byzantine music. Whereas the drone note does not typically change much during the course of chanting, there are various schools of practice as to how often it can change. Some prefer that the drone note is help essentially for the duration of a hymn whereas others are amenable to the drone note frequently changing every so often in order to add a variation to the produces sound. Today, one can find both of these approaches, however, the middle ground of occasional changes to the drone note seems to prevail more in practice.

Unlike western music in which the notes on a staff can be individually identified, Byzantine music is referential and, therefore, a neume can only be identified depending on the previous neume. The neumes allow the chanter to know how many intervals ones must jump either up or down. To a degree this makes Byzantine music more complex since if one were to make a mistake reading a neume, but was unaware of their error, then one could conceivably continue their error by misinterpreting subsequent neumes. At any rate, the beginning of any Byzantine music piece will have an identifying character indicating the mode in which the hymn is to be chanted. This also informs the chanter as to the starting note. The nuemes that follow help to guide the notes of the chanted hymn and additional features within the musical text give indications as to the value of a note, potential key changes, and other elements one finds in more complex music.

Another key aspect of Byzantine music which is not well regulated is the speed of hymns. Whereas in western music there is typically a specific tempo for a song which can be more precisely regulated by a metronome, no such precision exists in Byzantine music. There are, however, certain types of classifications which help to regulate a hymn’s overall speed. These three classifications are papadic (very slow), sticheraric (medium pace/about four notes per syllable), and heirmologic (faster tempo). Often times, but not always, these classifications will correspond to the type of hymn being chanted unless there are extenuating circumstances such as an extended vigil in which most of the hymns are typically slower.

Byzantine music has developed over the centuries from a more simple and monotone expression of its hymnology to an increasingly more complex expression. There is precious little evidence from this early period stretching from the 4th–9th centuries since Byzantine music manuscripts are almost non-existent and the vast majority of evidence can only be deduced from historical accounts, sermons, or clues within later liturgical books, however, there are some examples of hymns that are known to have come from this era even though their present form are probably more ornate than their original. Hymns such as “ΦῶςἹλαρόν” (O Gladsome Light) are known to have been dated to at least the 4th century.

During the medieval ages, Byzantine music probably did not change that much due to a desire to remain faithful to the tradition passed down. This can be particularly seen in the usage of multiple “θέσεις” (theses) which are groups of musical notes often used in the same hymn and frequently throughout the mode in general. As of the 9th century, however, we start to see Byzantine music manuscripts with a written hymnographical tradition. Though evidence suggests that Byzantine music did not change very much in the first several centuries of its existence, it did undergo changes especially towards the end of the Byzantine Empire and during the Ottoman occupation of former Byzantine territories. These changes include a mix of some more conservative elements while other elements are more liberal and subject to change. What is evident, however, is that the written notation became increasingly complex until about the early 19thcentury when there was a movement to simplify the written manner of Byzantine music to be more comprehensible to those who desired to study it. It is this later form of written music which has, more or less, been in use to this day.

Today, Byzantine music has once again gained in popular appeal in various regions. An example of this can be seen in the United States. About thirty to forty years ago the prevailing practice in liturgical services among the parishes of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America (an Eparchy of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople) was for a choir to sing the crudely adapted hymns to a polyphonic musical score. Thanks to some members of the hierarchy who value this sacred tradition as well as the extraordinary work of several professors of Byzantine chant at the Archdiocese’s theological school, a renewed interest in Byzantine music has produced an increase of parishes returning to this tradition, conferences on Byzantine music, a certificate program specifically for these studies, as well as a new generation of young Greek Orthodox Christians who are becoming increasingly competent in this field.

Even beyond the Orthodox world, Byzantine music has seen a growth in interest as it has become more accessible to the general populace and increased focus has been shed on this ancient tradition in academic settings. Furthermore, recordings from monastic communities, including from the convent of Ormylia in Greece and from the famously reclusive monks of Mount Athos, have given people from throughout the world the ability to hear the heavenly hymns that the Orthodox Church has been chanting for centuries.

With UNESCO’s recent decision to recognize Byzantine chant as being a part of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity, there is the hope that greater exposure will be brought to this art. For Orthodox Christians Byzantine chant constitutes a means by which we praise God and are brought into closer relation with Him through worship. But the desire to preserve Byzantine chant should have a wider appeal even for those who are not of the Orthodox faith since it constitutes the sacred tradition of a people who are disappearing. While this tradition may be seeing a revival in other parts of the world, the region in which it was given life, principally, Asia Minor, the Middle East, and Northeastern Africa, has experienced a quickly decreasing Christian populace often times due to war and persecution. Thus, the preservation and protection ofByzantine musicis the preservation of history itself and the memory of those persons throughout the centuries who lived this tradition.Most importantly, however, by preserving the psaltic art, we acknowledge the courageof those who still carry on this sacred hymnologicaltradition even as they face violence for lifting their voices to the Lord.